How Replicache Works

If your goal is to start using Replicache immediately without having to understand all the details, just read The Big Picture section and return to the other sections as needed.

The Big Picture

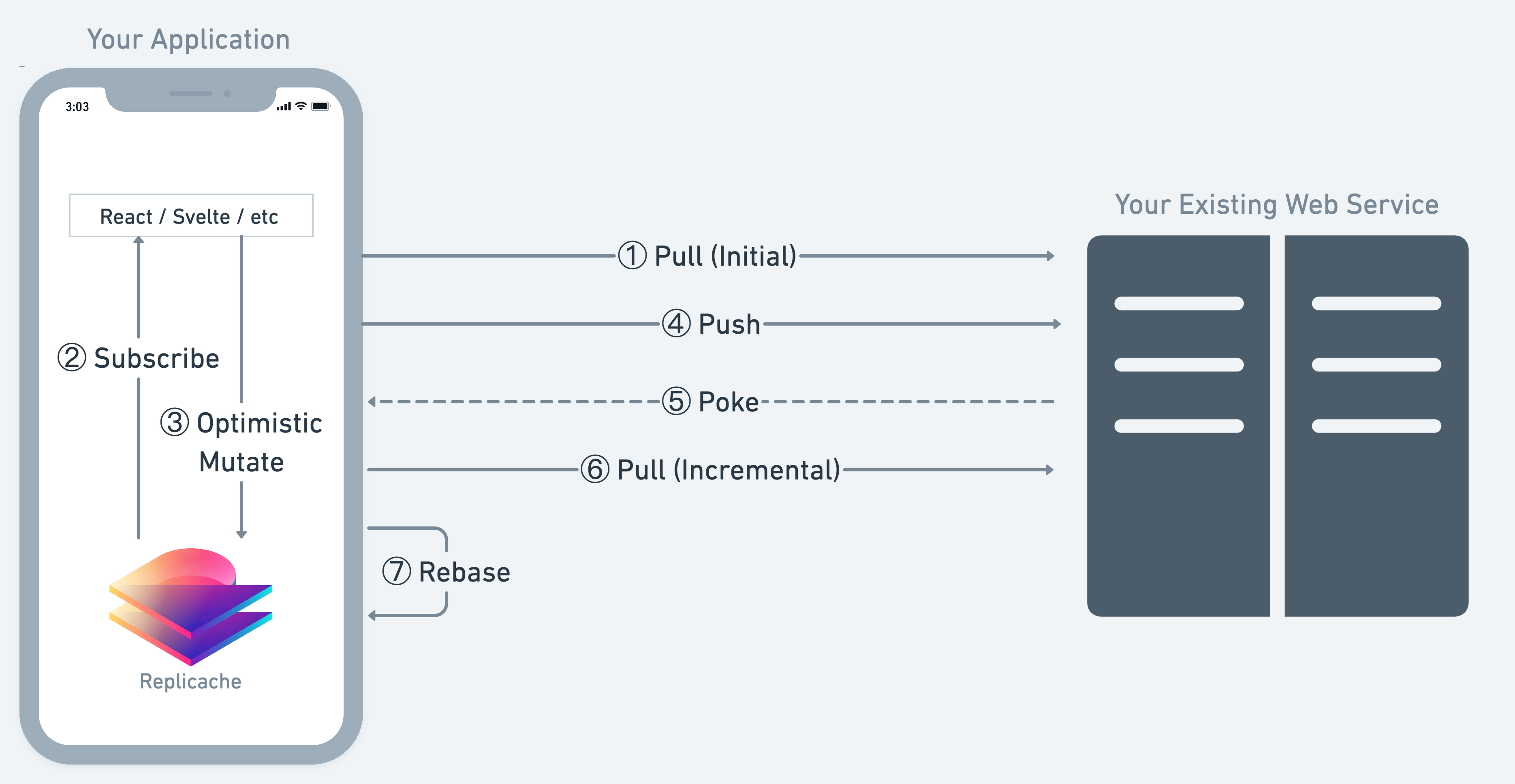

Replicache enables instantaneous UI and realtime updates by taking the server round-trip off the application’s critical path, and instead syncing data continuously in the background.

The Replicache model has several parts:

Replicache: an in-browser persistent key-value store that is git-like under the hood. Your application reads and writes to Replicache at memory-fast speed and those changes are synchronized to the server in the background. Synchronization is bidirectional, so in the background Replicache also pulls down changes that have happened on the server from other users or processes. The git-like nature of Replicache enables changes flowing down from the server to be merged with local changes in a principled fashion. A detailed understanding of how this works is not required to get started; if you wish, you can read more about it in the Sync Details section.

Your application: your application stores its state in Replicache. The app is implemented in terms of:

- Mutators: JavaScript functions encapsulating change and conflict resolution logic. A mutator transactionally reads and writes keys and values in Replicache. You might have a mutator to create a TODO item, or to mark an item done.

- Subscriptions: subscriptions are how your app is notified about changes to Replicache. A subscription is a standing query that fires a notification when its results change. Your application renders UI directly from the results of subscription notifications. You might for example have a subscription that queries a list of items so your app gets notified when items are added, changed, or deleted.

Your server: Your server has a datastore containing the canonical application state. For example, in our Repliear sample this is a Postgres database running on Heroku, but many other backend stacks are supported. The server provides up- and downstream endpoints that users’ Replicaches use to sync.

- Push (upstream): Replicache pushes changes to the push endpoint. This endpoint has a corresponding mutator for each one your application defines. Whereas the client-side mutator writes to the local Replicache, the push endpoint mutator writes to the canonical server-side datastore. Mutator code can optionally be shared between client and server if both sides are JavaScript, but this is not required. As we will see, changes (mutator invocations aka mutations) that have run locally against Replicache are re-run on the server when pushed.

- Pull (downstream): Replicache periodically fetches the latest canonical state that the server has from the pull endpoint. The endpoint returns an update from the state that the local Replicache has to the latest state the server has, in the form of a diff over the key-value space they both store.

- Poke: While Replicache will by default pull at regular intervals, it is a better user experience to reflect changes in realtime from one user to the others. Therefore when data changes on the server, the server can send a poke to Replicache telling it to initiate a pull. A poke is a contentless hint delivered over pubsub to all relevant Replicaches that they should pull. Pokes can be sent over any pubsub-like channel like Web Sockets or Server-Sent Events.

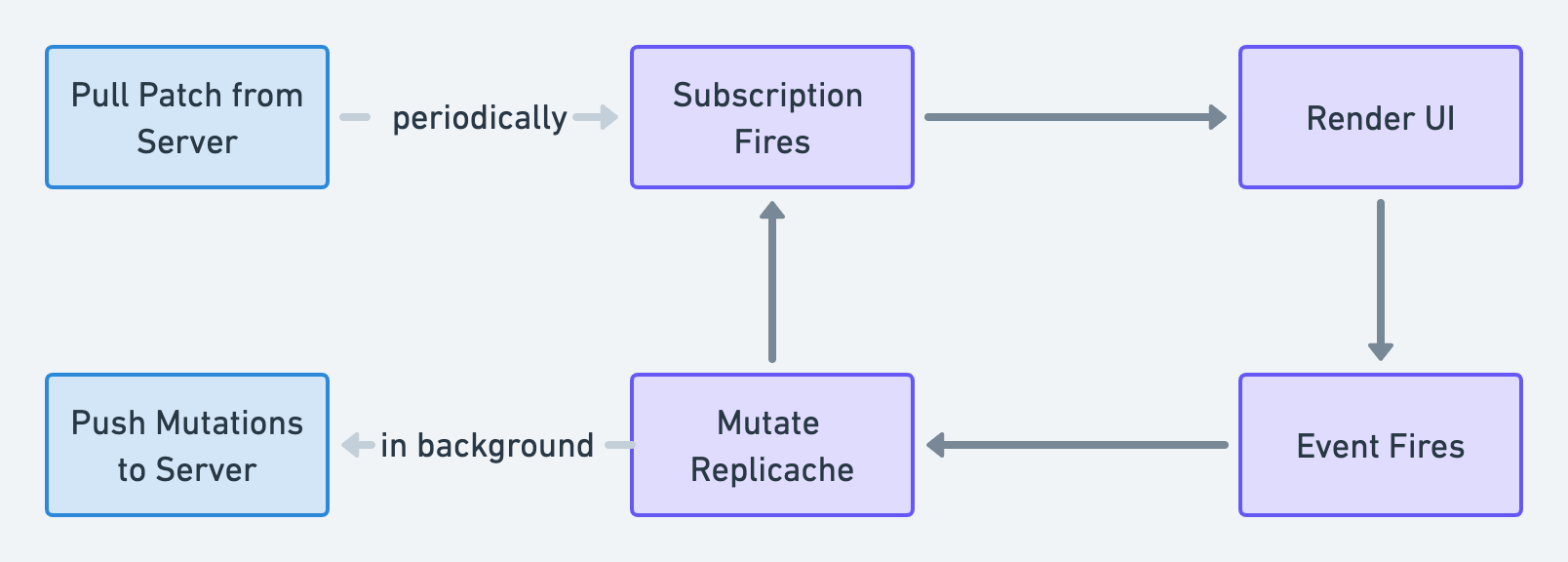

Sync: When a user takes an action in your app, the app invokes a mutator. The mutator modifies the local Replicache, and your subscriptions fire to update your UI. In the background, these changes are pushed to the server in batches, where they are run using the server-side mutators, updating the canonical datastore. When data changes on the server, the server pokes connected Replicaches. In response, Replicache pulls the new state from the server and reveals it to your app. Your subscriptions fire because the data have changed, which updates your app’s UI.

The sync process happens in a principled fashion such that:

- local changes are guaranteed to get pushed to the server

- changes pulled from the server are merged with local changes in a sensible and predictable way. For example if a user creates a TODO item, Replicache guarantees that all users including the author see it created exactly once, and with the same results.

Clients, Client Groups, and Caches

An instance of the Replicache class in memory is called a client.

import {Replicache} from "replicache";

const rep = new Replicache({

name: userID,

...

});

console.log(rep.clientID);

A client is identified by a unique, randomly generated clientID. There is typically one client (instance of Replicache) per tab. A client is ephemeral, being instantiated for the lifetime of the application in the tab. The client provides fast access to and persistence for the keys and values used by the application.

A client group is a set of clients that share data locally. Changes made by one client are visible to other clients, even while offline. Client groups are identified by a unique, randomly generated clientGroupID.

Under normal circumstances, all clients within the same browser profile are part of a single client group. For brief periods during schema migrations, two client groups can coexist in the same browser profile.

The client group sits on top of an on-disk persistent cache identified by the name parameter to the Replicache constructor. All clients in the group that have the same name share access to the same cache.

It’s important that each user of your application uses a different Replicache name. That way, different users will have separate caches. This ensures that different users within the same browser profile never see or modify each others' data.

The Client View

Each client keeps an ordered map of key/value pairs called the Client View that is persisted in the underlying cache. Client View keys are strings and the values are JSON-compatible values. The Client View is the application data that Replicache syncs with the server. We call it the "Client View" because different clients might have different views of the state of the server. For example, a user's Client View might contain per-user state that is only visible to them.

The size of a Client View is limited primarily by browser policies. You can store hundreds of MB in a Replicache Client View without affecting performance significantly, though HTTP request limits to your endpoints might come into play.

Access to the Client View is fast. Reads and writes generally have latency < 1ms and data can be scanned at over 500MB/s on most devices.

You do not need to keep a separate copy of the client view in memory (e.g., useState in React). The intent is that you read data out of Replicache and directly render it. To make changes, you modify Replicache using mutators (see below). When mutators change keys or values in the Client View, Replicache fires subscriptions that cause the UI to re-read the relevant data and re-render the UI.

Subscriptions

UI is typically built using the subscribe() method (or useSubscribe() in React):

const todos = useSubscribe(rep, async tx => {

return await tx.scan({prefix: 'todo/'}).toArray();

});

return (

<ul>

{todos.map(todo => (

<li key={todo.id}>{todo.text}</li>

))}

</ul>

);

The subscribe method gets passed a function that receives a ReadTransaction parameter. You can do any number of reads from Replicache inside this function, and compute some result.

Whenever the data in Replicache changes such that a subscription is potentially out of date — either because of a local/optimistic change or because of syncing with the server — the subscription function re-runs. If the result changes, the subscription fires and the UI re-renders.

By using subscriptions to build your UI, you guarantee that the entire UI always correctly reflects the latest state, no matter why or how it changed.

Mutations

Mutations are the way that data changes in Replicache, and are at the core of how Replicache sync works.

At startup, register one or more mutators with Replicache. A mutator is a named JavaScript function that operates on Replicache. Both createTodo and markTodoComplete below are mutators.

const rep = new Replicache({

...

mutators: {

createTodo,

markTodoComplete,

},

});

async function createTodo(tx: WriteTransaction, todo: Todo) {

await tx.set(`/todo/${todo.id}`, todo);

}

async function markTodoComplete(tx: WriteTransaction,

{id, complete}: {id: string, complete: boolean}) {

const key = `/todo/${id}`;

const todo = await tx.get(key);

if (!todo) {

return;

}

todo.complete = complete;

await tx.set(key, todo);

}

To change the Client View, call a mutator and pass it arguments:

await rep.mutate.createTodo({id: nanoid(), text: "take out the trash"});

...

await rep.mutate.markTodoComplete({id: "t1", complete: true});

This applies the changes to the Client View, causing any relevant subscriptions to re-run and fire if necessary. In React, this will cause the dependent components to re-render automatically.

Internally, calling a mutator also creates a mutation: a record of a mutator being called with specific arguments. For example, after the above code runs, Replicache will internally be tracking two mutations:

[

{id: 1, name: "createTodo", args: {id: "t1", text: "take out the trash"}},

{id: 2, name: "markTodoComplete", args: {id: "t1", complete: true}},

]

Until the mutations above are pushed by Replicache to the server during sync they are pending (optimistic).

Sync Details

The above sections describe how Replicache works on the client-side. This is all you need to know to get started using Replicache using the Todo starter app. That’s because the starter app includes a generic server that fully implements the sync protocol.

However, to use Replicache well, it is important to understand how sync works conceptually. And you need to know this if you plan to modify the server, use Replicache with your own existing backend, or swap out the datastore.

In the following discussion we use "state" as shorthand for "the state of the key-value space", the set of keys that exist and their values. We often say that some state is used as a "base" for a change, or that a change is applied "on top of" a state. By this we simply mean that the change is made with the base state as its starting input.

The Replicache Sync Model

The "sync problem" that Replicache solves is how to enable decoupled, concurrent changes to a key-value space across many clients and a server such that:

- the key-value space kept by the server is the canonical source of truth to which all clients converge.

- local changes to the space in a client are immediately (optimistically) visible to the app that is using that client. We call these changes speculative, as opposed to canonical.

- local changes can be applied (in the background) on the server such that:

- a change is applied exactly once on the server, with predicable results and

- new changes that have been applied on the server can sensibly be merged with the local state of the key-value space

The last item on the list above merits taking a moment to expand upon and internalize. In order to sensibly merge new state from the server with local changes, the client must account for any or all of the following cases:

- A local change in the client has not yet been applied to the server. In this case, Replicache needs to ensure that this local change is not "lost" from the app's UI in the process of updating to the new server state. In fact, as we will see, Replicache effectively re-runs such changes "on top of" the new state from the server before revealing the new state to the app.

- A local change in the client has already been applied to the server in the background. Yay. The effects of this local change are visible in the new state from the server, so Replicache does not need to re-run the change on the new state. In fact, it must not: if it did, the change would be applied twice, once on the server and then again by the client on top of the new state already containing its effects.

- Some other client or process changed part of the key-value space that the client has. Since the server's state is canonical and the client's is speculative, any local changes not yet applied on the server must be re-applied on top of the new canonical state before it is revealed. This could modify the effect of the local unsynchronized change, for example if some other user marked an issue "Complete" but locally we have an unsynchronized change that marks it "Will not fix". Some logic needs to run to resolve the merge conflict. (Spoiler: mutators contain this logic. More on this below.)

How Replicache implements these steps is explained next.

Local execution

When a mutator is invoked, Replicache applies its changes to the local Client View. It also queues a corresponding pending mutation record to be pushed to the server, and this record is persisted in case the tab closes before it can be pushed. When created, a mutation is assigned a mutation id, a sequential integer uniquely identifying the mutation in this client. The mutation id also describes a causal order to mutations from this client, and that order is respected by the server.

Push

Pending mutations are sent in batches to the push endpoint on your server (conventionally called replicache-push).

Mutations carry exactly the information the server needs to execute the mutator that was invoked on the client. That is, the order in which the mutations were invoked (in order of mutation id), the clientID that the mutation was created on, the name of the mutator invoked, and its arguments. The push endpoint executes the pushed mutations in order by executing the named mutator with the given arguments, canonicalizing the mutations' effects in the server's state. It also updates the corresponding last mutation id for the client that is pushing. This is the high water mark of mutations seen from that client and is information used by the client during pull so that it knows which mutations need to be re-run on new server state (namely, those with mutation ids > the server's last mutation id for the client).

Speculative Execution and Confirmation

It is important to understand that the push endpoint is not necessarily expected to compute the same result that the mutator on the client did. This is a feature. The server may have newer or different state than the client has. That’s fine —- the pending mutations applied on the client are speculative until applied on the server. In Replicache, the server is authoritative. The client-side mutators create speculative results, then the mutations are pushed and executed by the server creating confirmed, canonical results. The confirmed results are later pulled by the client, with the server-calculated state taking precedence over the speculative result. This precedence happens because, once confirmed by the server, a speculative mutation is no longer re-run by the client on new server state.

Pull

Periodically, Replicache requests an update to the Client View by calling the pull endpoint (conventionally, replicache-pull).

The pull request contains a cookie and a clientGroupID, and the response contains a new cookie, a patch, and a set of lastMutationIDChanges.

The cookie is a value opaque to the client identifying the canonical server state that the client has. It is used by the server during pull to compute a patch that brings the client’s state up to date with the server’s. In its simplest implementation, the cookie encapsulates the entire state of all data in the client view. You can think of this as a global “version” of the data in the backend datastore. More fine-grained cookie versioning strategies are possible though. See [/concepts/strategies/overview](Backend Strategies) for more information.

The lastMutationIDChanges returned in the response tells Replicache which mutations have been confirmed by the server for each client in the group. Those mutations have their effects, if any, represented in the patch. Replicache therefore discards any pending mutations it has for each client with id ≤ lastMutationID. Those mutations are no longer pending, they are confirmed.

Rebase

Once the client receives a pull response, it needs to apply the patch to the local state to bring the client's state up to date with that of the server.

But it can’t apply the patch to the current local state, because that state likely includes changes caused by pending mutations. It's not clear what a general strategy would be for applying the patch on top of local changes. So it doesn't. Instead, hidden from the application's view, it rewinds the state of the Client View to the last version it got from the server, applies the patch to get to the state the server currently has, and then replays any pending mutations on top. It then atomically reveals this new state to the app, which triggers subscriptions and the UI to re-render.

In order to support the capability to rewind the Client View and apply changes out of view of the app, Replicache is modeled under the hood like git. It maintains historical versions of the Client View and, like git branches, has the ability to work with a historical version of the Client View behind the scenes. So when the client pulls new state from the server, it forks from the previous Client View received from the server, applies the patch, rebases (re-runs) pending mutations, and then reveals the new branch to the app.

It’s possible and common for mutations to calculate a different effect when they run during rebase. For example, a calendar invite may run during rebase and find that the booked room is no longer available. In this case, it may add an error message to the client view that the UI displays, or just book some different but similar room.

Poke (optional)

Replicache can call pull on a timer (see pullInterval) but this is really only used in development. It’s much more common for the server to tell potentially-affected clients when a good time to pull is.

This is done by sending the client a hint that it should pull soon. This hint message is called a poke. The poke doesn’t contain any actual data. All the poke does is tell the client that it should pull again soon.

There are many ways to send pokes. For example, the replicache-todo starter app does it using Server-Sent Events. However, you can also use Web Sockets, or a push service like Pusher.

Conflict Resolution

The potential for merge conflicts is unavoidable in a system like Replicache. Clients and the server operate on the key-value space independently, and all but the most trivial applications will feature concurrent changes by different clients to overlapping parts of the keyspace. During push and pull, these changes have to merge in a way that is predictable to the developer and makes sense for the application. For example, a meeting room reservation app might resolve a room reservation conflict by allocating a room to the first party to land the reservation. One change wins, the other loses. However, the preferred merge strategy in a collaborative Todo app where two parties concurrently add items to a list might be to append both of the items. Both changes "win."

The potential for merge conflicts arises in Replicache in two places. First, when a speculative mutation from a client is applied on the server. The state on the server that the mutation operates on could be different from the state it was originally applied on in the client. Second, when a speculative mutation is rebased in the client. The mutation could be re-applied on state that is different from the previous time it ran.

Replicache embraces the application-specific nature of conflict resolution by enabling developers to express their conflict resolution intentions programmatically. Mutators are arbitrary JavaScript code, so they can programmatically express whatever conflict resolution policy makes the most sense for the application. To take the previous two examples:

- a

reserveRoommutator when run locally for the first time might find a room in stateAVAILABLE, and mark it asRESERVEDfor the user. Later, when run on the server, the mutator might find that the room status is alreadyRESERVEDfor a different user. The server-executed mutator here takes a different branch than it did when run locally: it leaves the room reservation untouched and instead sets a bit in the user's state indicating that their attempt to book the room failed. When the user's client next pulls, that bit is included in the Client View. The app presumably has a subscription to watch for this bit being set, and the UI shows the room as unavailable and notifies the user that the reservation failed. - an

addItemmutator for a Todo app might not require any conflict resolution whatsover. Its implementation can simply append the new item to the end of whatever it finds on the list!

We believe the Replicache model for dealing with conflicts — to have defensively written, programmatic mutation logic that is replayed atop the latest state — leads to few real problems in practice. Our experience is that it preserves expressiveness of the data model and is far easier to reason about than other general models for avoiding or minimizing conflicts.